With the ‘polar vortex’ that held much of North America in its frigid grip last week, it was interesting for this ‘girl of the north’ listen to southerners goggle about phenomena that I’ve been experiencing for most of my life.

I found one event, in particular, rather interesting. Last week, the media and thus a large portion of the population, was introduced to the concept of ‘frost quakes’. Torontonians were rattled out of their beds by thunderous booms that shook parts of the city at random intervals. Soon the headlines were reading that it was so cold in Canada, the ground was cracking.

Large crevasse in the rock, likely split apart by frost action

Having spent a number of winters on the shores of Lake Winnipeg, where temperatures regularly dip below -30C, I’ve seen first-hand the power of ice and its ability to snap rock in two. Ice expands and contracts with temperature fluctuations. It also becomes less flexible as it becomes colder. Water that finds its way into fissures in the rock or soil can push so hard went it freezes – especially if the temperature drops quickly – that the substrate buckles under the pressure. Here, along the lake, the limestone cliffs are full of cracks forced open by winter’s icy push. Still, these earth-shattering events are extremely rare. You don’t usually see new cracks on a yearly basis.

However, there is another type of frost quake, or ice quake, as I prefer to call them that happens considerably more often. Based on where the events were reported last week along Lake Ontario, I’m willing to bet that it was this type of cryoseism that residents heard for the most part. While the ground doesn’t crack very often, the ice on the lake does. On large lakes, like Lake Winnipeg or Ontario, a sudden snap of the ice can sound like a cannon shot, nearly knocking you off your feet and rattling windows in their panes. While it’s still not something you experience everyday, such quakes happen on Lake Winnipeg fairly regularly.

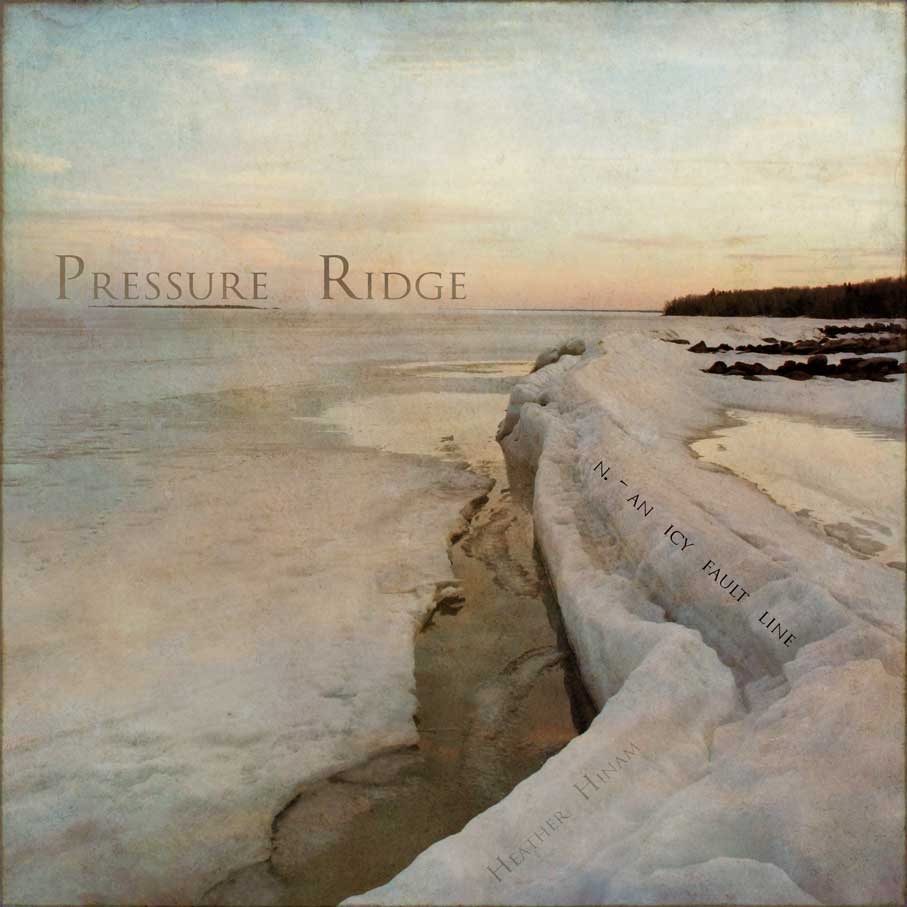

That’s because this 23,750 sq km lake freezes completely to a depth of at least a metre every year. That much surface area can’t solidify into one piece. So it freezes into floes that knit together much like the tectonic plates of the earth did when the crust first formed. Like the earth’s crust, the lake’s surface is full of fault lines, or pressure ridges. These giant cracks can run for kilometres along the lake and usually form in about the same place every year. Some ridges, known as stamukhi, are grounded along the shoreline, where ice that is held fast to the shore meets the free-flowing ice of deeper waters, while others run along over top of varying depths.

Even frozen, the lake is very much alive and pressure ridges are the sites where this is most noticeable. It’s along these lines that the ice floes move, sliding along, away from and into each other. A particularly violent collision is like a mini mountain building event and along with an ice quake, you will also see a ridge of ice has been pushed sometimes more than 2 meters into the air. More often, however, the two floes simply press against each other, expanding and contracting like long, drawn-out breaths as the temperatures wax and wane. Eventually, the pressure overtakes the compressive strength of the ice and the ridge snaps in a startling bang that is often followed by the gentle whale-like ‘whoom’ sounds of the pressure waves dissipating through the rest of the ice.

As fascinating as they are, pressure ridges are also dangerous places to be. The ice floes can slide away from each other just as quickly as they can come together and loose plates of ice can trick the unwary into thinking they are still on solid ground. A number of commercial ice fishermen have been lost through shifting ridges over the last century on the lake.

Unless you live along a lake that freezes regularly, Ice quakes are truly something few people get to experience. So, I’m glad that our recent continental cold snap gave more people the chance to learn a bit more about this fascinating phenomena and remember just how powerful nature can be.

Growing up, I would hear people quote this statistic: “Eskimos have more than a hundred words for snow.” Actually, I still hear people rattle off this little ‘fact’, especially in winter. However, there are a lot of problems with this statement, not even including the fact that the indigenous people of North America’s tundra and Arctic regions are known as Inuit, not Eskimo. No, what really grates on me about this blanket statement is the implication that it’s somehow weird to have so many words to describe one thing.

Growing up, I would hear people quote this statistic: “Eskimos have more than a hundred words for snow.” Actually, I still hear people rattle off this little ‘fact’, especially in winter. However, there are a lot of problems with this statement, not even including the fact that the indigenous people of North America’s tundra and Arctic regions are known as Inuit, not Eskimo. No, what really grates on me about this blanket statement is the implication that it’s somehow weird to have so many words to describe one thing.