It was minus 40 Celsius with the wind chill the other morning. The bite of the air stung any carelessly exposed skin and the snow squeaked like Styrofoam underfoot. Wrapped up in my shearling coat, I couldn’t help but watch in fascination as a nearby mountain ash came alive with foraging Pine Grosbeaks and the cheerful chirps of chickadees and nuthatches filled the frosty air, reminding me just how incredible these tiny winter residents really are.

It was minus 40 Celsius with the wind chill the other morning. The bite of the air stung any carelessly exposed skin and the snow squeaked like Styrofoam underfoot. Wrapped up in my shearling coat, I couldn’t help but watch in fascination as a nearby mountain ash came alive with foraging Pine Grosbeaks and the cheerful chirps of chickadees and nuthatches filled the frosty air, reminding me just how incredible these tiny winter residents really are.

Chickadees, for example, weigh not much more than 10 g, about the same as two nickles. Yet, they can survive quite comfortably in temperatures that would leave us frostbitten and shivering.

Winter birds accomplish this seemingly unfathomable feat in a number of different ways. Firstly, they’re wearing a down coat. Those of you who own one know just how warm they can be and for birds, that insulation is part of the standard package. Feathers are a remarkable insulator. Comprising only about 5 – 7 % of a bird’s body weight (that’s half a gram on a chickadee), the air trapped within them makes up 95% of that weight’s volume, creating a thick layer of dead air that traps heat generated by the body, preventing much of its loss even on the coldest of days. Many winter residents grow a thicker winter coat, much like mammals, augmenting their feather count by up to 50 %. Fluffing feathers increases their insulation factor even further (about 30%), making them a very efficient way to keep warm in the winter, so efficient, in fact, some birds, like Great Gray Owl can actually overheat in the summer.

While some species, like Ruffed Grouse and many owls, grow feathers, along their legs and feet, like fluffy winter boots, most songbirds’ legs are bare, thin sticks of sinew, blood and bone exposed to the elements. Although birds can tuck these delicate structures up into the warm cover of down when temperatures really plummet, most of the time they’re out in the open. So, why don’t they freeze and why isn’t all of a bird’s body heat lost through these naked limbs? Bird legs are marvels of biological efficiency, having been streamlined by millennia of evolution into sleek structures with very little muscle and few nerves, using instead pulley systems of tendons and bone to accomplish movement. These tissues, along with their scaly coverings have very little moisture and are less likely to freeze than flesh and skin.

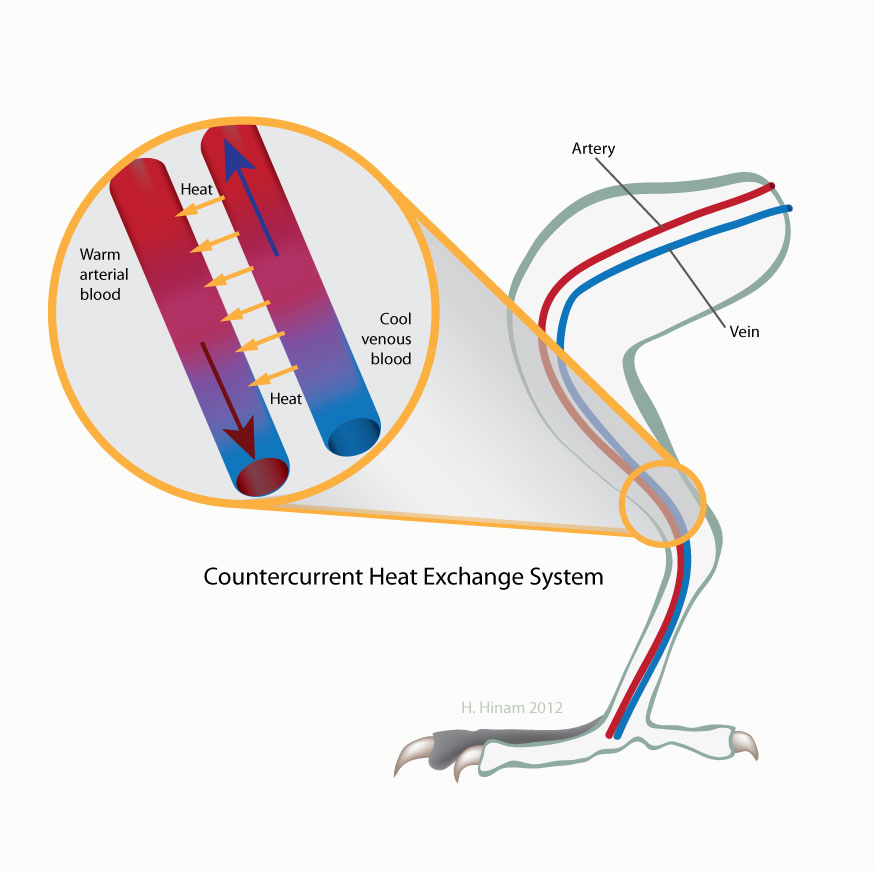

Birds also have cold feet. Using a common natural system called a countercurrent heat exchange, our feathered friends keep their feet upwards of ten to twenty degrees colder than their core body temperature.  Warm arterial blood on its way to the feet pass right next to colder blood coming back towards the body through the veins. Heat wants to reach a point of equilibrium, so warmth from the arteries passes into the veins which carries it back into the body. Because the flows are running opposite to each other, it’s impossible for the heat balance to ever reach equilibrium, so by the time the blood gets to the feet, it’s much cooler than when it entered the leg and all that precious body heat has been kept where it needs to be, in the core.

Warm arterial blood on its way to the feet pass right next to colder blood coming back towards the body through the veins. Heat wants to reach a point of equilibrium, so warmth from the arteries passes into the veins which carries it back into the body. Because the flows are running opposite to each other, it’s impossible for the heat balance to ever reach equilibrium, so by the time the blood gets to the feet, it’s much cooler than when it entered the leg and all that precious body heat has been kept where it needs to be, in the core.

However, as most of us who have experienced a true northern winter know, a coat alone isn’t always enough. There has to be heat to trap in order for insulation to work over the long term. To generate that heat, many winter birds shiver constantly when they’re not moving. Ravens, whose feather count isn’t as high as some of its more fluffy distant cousins, actually shiver constantly, even when flying, the repeated contractions of their massive pectoral muscles acting like a furnace. Powering that furnace takes energy and cold-weather specialists meet those needs by upping their metabolic rate, in some species, to several times their normal levels. As a result, food is always a going concern in winter.

Many winter residents can only forage for food during the day, so keeping the internal fires burning at night can be a challenge. Finding a warm place to settle in for the night reduces those metabolic needs. Densely-packed spruce boughs or old tree cavities are perfect nighttime microclimates and many birds use them. Chickadees will often take it a step further, piling as many fluffy little birds as possible into an old woodpecker hole to share body heat, which may just be too much cuteness in one place. Ruffed Grouse take advantage of the insulative capacity of snow in a somewhat comical way. One cold nights, the birds dive head first into a drift and tunnel deeper into the snow, creating a cave known as a kieppi. Temperatures inside the kieppi can hover just around the freezing mark, even when it’s minus thirty outside.

So as we close in on the shortest day of the year and sink deeper into the cold clutches of winter, take a moment, now and then, to marvel at those tiny survivalists outside your window. Much of the technology that keeps us from succumbing to winter’s icy grip was adapted from them. Nature truly is our greatest teacher.