Since the beginning of January, I’ve had the pleasure of teaching a second-year Chordate Zoology course at the University of Winnipeg. Having taken it at a different school as an undergrad and having taught the labs several years ago, the material isn’t exactly new. However, it’s been a wonderful way to rediscover the fascinating story that is the evolution of vertebrates.

Since the beginning of January, I’ve had the pleasure of teaching a second-year Chordate Zoology course at the University of Winnipeg. Having taken it at a different school as an undergrad and having taught the labs several years ago, the material isn’t exactly new. However, it’s been a wonderful way to rediscover the fascinating story that is the evolution of vertebrates.

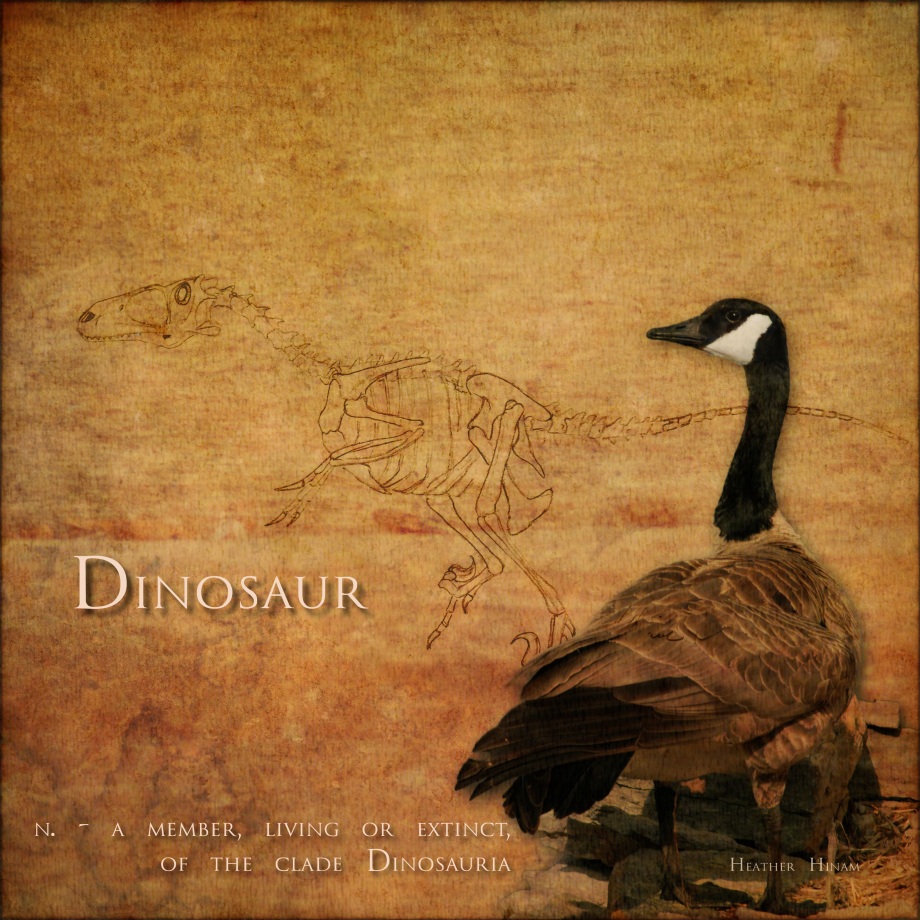

First and foremost, it’s reminded me that we see dinosaurs just about everyday, flitting through the trees, soaring high overhead and gliding across a glassy pond. They’re all around us, bringing colour and music to our world.

Because of my grounding in zoology, the concept that birds are dinosaurs is not new to me, nor is it difficult to understand. However, I imagine for many people it’s a bit of a challenge to make the mental leap from a chickadee flitting among the leaves to a giant Tyrannosaurus rex thundering along a Cretaceous plain. Still, whether you can see the resemblance or not, the genetic relationship is undeniable. A spectacularly rare discovery in 2007 of intact collagen protein in the fossil leg bone of a T-Rex allowed researchers to compare the amino acid chains within with a database of species we already have sequences for. It turned out that of all the possibilities, from mammals to reptiles, the sequence was most closely related to the collagen sequence of a chicken. This discovery probably would’ve left good ol’ Colonel Sanders with nightmares!

Even without the molecular connection, you can still see the family resemblance. Birds are descended from a lineage of dinosaurs known as Theropods, swift, bipedal predators, like Velociraptor, Deinonychus (pictured above) and the aforementioned T. Rex. While the ones most people are familiar with, thanks to Jurassic Park, are the large, ferocious creatures, most of this lineage were rather small, adapted for running and pouncing on their prey. These adaptations for speed and agility can still be seen in the skeletons of the last remaining dinosaurs, the birds.

They walked on two legs, their limbs swinging back and forth on the fulcrum of a pelvis that looked like part of a bicycle. Over time, that pelvis shifted, the individual bones fusing and getting stonger to withstand the strain brought by high speeds while maintaining its light weight. In fact, weight reduction was the order of the day in the evolution of birds from their theropod ancestors. Bones, overall, got smaller, lighter, hollowing out into tubes that were, and still are, reinforced by thin struts called trabeculae. The pectoral girdle got both smaller and in some ways, more rigid. Where the scapulae were freed up to allow the arms to swing out like flapping wings, the clavicles fused, forming the furcula (wishbone) and the sternum developed a deep keel, giving more space for what eventually became flight muscles to attach.

Still, the most striking feature these dinosaurs had in common with the ones we see today was feathers. That’s right, Creighton missed that little detail. Many theropods, Velociraptor included, had feathers. They started out as long, thin fibers that offered the minimum of insulation, gradually developing into the differentiated flight, covert and down feathers we know now. They appeared at least 160 million years ago, long before Archaeopterix (the first official bird) and even non-avian theropods like Velociraptor and Deinonychus. Paleontologists have found them in numerous species, including a small chicken-like theropod (the whole protein thing is making sense now) named Anchiornis. They’ve even managed to determine the colour of the feathers by examining the shape of the melanosomes (tiny pockets of pigment) preserved in the fossilized remains.

As more and more of these characteristics are teased from the fossil record, I can’t help but hope that one day my field guide to birds includes a section on the species that paved the genetic way for the spectacular diversity we see today.